Since the beginning of April, intensive work has been done to set up a testing line at DTU aimed at increasing the COVID-19 test capacity in the Capital Region of Denmark. 1,500 tests are now being analysed daily, and the capacity will soon be increased to 5,000.

A testing system for COVID-19 has been set up in record time in the Centre for Diagnostics DTU’s DANAK-accredited laboratories. Just before Ascension Day, the first real samples arrived from Rigshospitalet (Copenhagen University Hospital), and DTU is now testing samples from both Rigshospitalet and Hvidovre Hospital.

The Centre has a long history of developing and conducting tests for diagnosis of animal diseases and it monitors avian influenza (bird flu), among other diseases. Therefore, the Centre was already geared to handle pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, which is the origin of the COVID-19 virus. And in just a month and a half, a testing line has been set up to analyse a number of the many COVID-19 samples taken in the Capital Region of Denmark.

Initially, the plan is to run 1,500 tests per day and—in line with the process becoming fully automated—the capacity can be extended as needed, for example up to as many as 5,000 tests a day. The tests initially come from Hvidovre Hospital and Rigshospitalet, but other hospitals in the region may subsequently provide samples.

A total of four teams of eight employees—laboratory technicians and scientific staff from the Centre for Diagnostics DTU, DTU Health Tech, DTU Biosustain, the National Food Institute, and DTU Aqua—are ready to keep the testing line running in two shifts from 7.30 a.m. to 10 p.m. seven days a week.

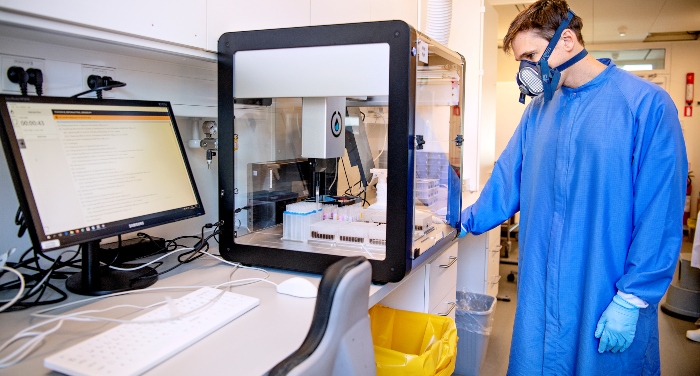

When the samples arrive, they are treated in a way that protects against infection by any Coronavirus contained in them. If employees nevertheless decide to wear a face mask, this is for protection against being infected by each other, even though there are strict rules on how many people can be assembled in each room at a time.

However, gloves are necessary, because humans always have so-called RNases on their fingers, which can break down the viral RNA and thus interfere with the test result.

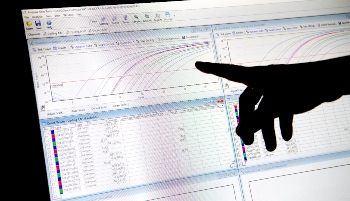

The samples are registered and scanned on arrival, so that they can be monitored by the digital information system on their journey through four laboratories and five robots.

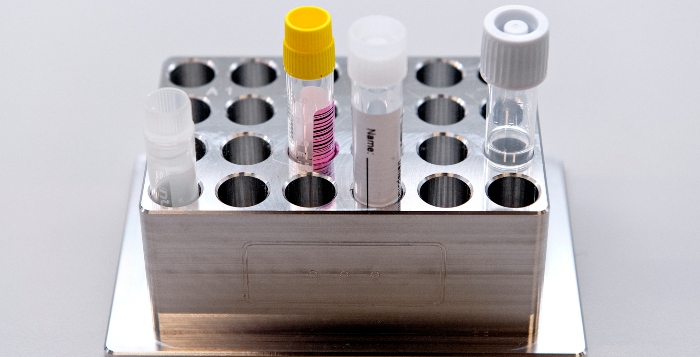

The biggest challenge faced by the testing line is the many changing types of test tubes arriving from the hospitals, as the robots have to be re-set for each tube type. The many types of test tubes reflect a total market shortage of all equipment used for Coronavirus testing lines worldwide, which means that hospitals have to procure the tubes that are available regardless of type. The specially designed metal blocks are 3D printed at DTU Mechanical Engineering. Workshop.

The blue colour recurs on doors, instruments, refrigerators, etc. in the COVID-19 laboratories, so that there is no doubt about where things belong.

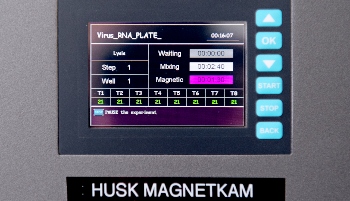

In the first laboratory, a robot puts the samples on plates. An employee then transfers them to station 2, where the viral RNA is purified and converted into a new format in yet another robot.

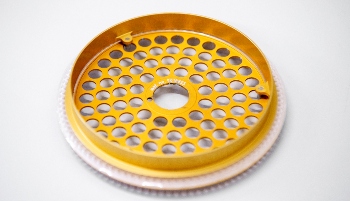

At COVID-19 station 3, virus RNA is transferred to PCR reagents in a new robot and the test ring is inserted into the PCR machine in station 4, where the next step—the so-called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)—is performed. Here, SARS-CoV-2-RNA is propagated into quantities that allow the presence of virus in the sample to be measured.

The day-to-day operation of the testing line is handled by Centre for Diagnostics DTU’s Head of Development Helene Larsen. Here she is standing at the PCR platform.

DTU’s PCR platform Rotorgene differs from those used in other laboratories, which means that the University’s test laboratory does not compete with hospitals for the most widely used test kits and plastic components.

Finally, the results are analysed by a scientific staff member. And the results are sent back to the hospitals via the Capital Region of Denmark’s database.